Stanley McChrystal, and David Silverman, Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World, first edition, New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin, 2015. A network of teams consists of a highly adaptable assembly of groups, which are united by a common purpose and work together in much the same way that the individuals on a single team collaborate (exhibit). Although the network of teams is a widely known construct, it is worth highlighting because relatively few companies have experience in implementing one. To promote rapid problem solving and execution under high-stress, chaotic conditions, leaders can organize a network of teams. Leaders can better mobilize their organizations by setting clear priorities for the response and empowering others to discover and implement solutions that serve those priorities. A small group of executives at an organization’s highest level cannot collect information or make decisions quickly enough to respond effectively. But in crises characterized by uncertainty, leaders face problems that are unfamiliar and poorly understood. In routine emergencies, the typical company can rely on its command-and-control structure to manage operations well by carrying out a scripted response. Organizing to respond to crises: The network of teamsĭuring a crisis, leaders must relinquish the belief that a top-down response will engender stability.

What leaders need during a crisis is not a predefined response plan but behaviors and mindsets that will prevent them from overreacting to yesterday’s developments and help them to look ahead. In this article, we explore five such behaviors and accompanying mindsets that can help leaders navigate the coronavirus pandemic and future crises.

What leaders need during a crisis is not a predefined response plan but behaviors and mindsets that will prevent them from overreacting to yesterday’s developments and help them look ahead. They might span a wide range of actions: not just temporary moves (for example, instituting work-from-home policies) but also adjustments to ongoing business practices (such as the adoption of new tools to aid collaboration), which can be beneficial to maintain even after the crisis has passed. Leonard, eds, Managing Crises: Responses to Large-Scale Emergencies, first edition, Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2009. During a crisis, which is ruled by unfamiliarity and uncertainty, effective responses are largely improvised. But they cannot respond as they would in a routine emergency, by following plans that had been drawn up in advance. Once leaders recognize a crisis as such, they can begin to mount a response. 3 Nahman Alon and Haim Omer, “The continuity principle: A unified approach to disaster and trauma,” American Journal of Community Psychology, 1994, Volume 22, Number 2, pp. Seeing a slow-developing crisis for what it might become requires leaders to overcome the normalcy bias, which can cause them to underestimate both the possibility of a crisis and the impact that it could have. Examples of such crises include the SARS outbreak of 2002–03 and now the coronavirus pandemic. It is a difficult step, especially during the onset of crises that do not arrive suddenly but grow out of familiar circumstances that mask their nature. Recognizing that a company faces a crisis is the first thing leaders must do. Gibbons, ed, Communicable Crises: Prevention, Response, and Recovery in the Global Arena, first edition, Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2007. Leonard, “Against desperate peril: High performance in emergency preparation and response,” in Deborah E. Indeed, the outbreak has the hallmarks of a “landscape scale” crisis: an unexpected event or sequence of events of enormous scale and overwhelming speed, resulting in a high degree of uncertainty that gives rise to disorientation, a feeling of lost control, and strong emotional disturbance. The massive scale of the outbreak and its sheer unpredictability make it challenging for executives to respond. The humanitarian toll taken by COVID-19 creates fear among employees and other stakeholders. The coronavirus pandemic has placed extraordinary demands on leaders in business and beyond. Separate articles describe organizing via a network of teams displaying deliberate calm and bounded optimism making decisions amid uncertainty demonstrating empathy and communicating effectively.

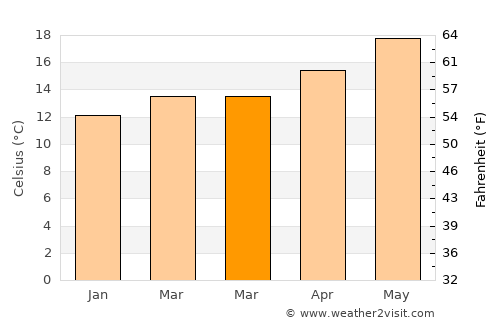

#Corona weather monday march 4 series

This article is the first in a series drawing together McKinsey’s collective thinking and expertise on five behaviors to help leaders navigate the pandemic and recovery.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)